Stakeholder management in public space projects-2018

Strategies for sustainable change: the Luz church road case in Chennai

Kavitha Selvaraj[1], Parama Roy[2] and Ashwin Mahalingam[3]

Abstract

It is widely accepted that effective stakeholder involvement is a precondition for successful implementation of all planning/developmental projects. In this paper, we use a participation-observation based case study of the Luz Church Road redesigning project in Chennai to highlight that the need for broad, deep, and long-term process of stakeholder involvement that existing literature eludes to is particularly relevant for public space projects. This is because governance, use, and appropriation of such spaces is diffused in the hands of multiple stakeholders and largely depends on development of a sense of ownership of the space and the rules/norms of the space. Drawing on existing literature and the case study, we propose a conceptual framework for an ideal lifecycle process of stakeholder management particularly relevant for public space projects.

Introduction

Urban planning, urban geography, and management studies literature have emphasized the importance of collaborative/participatory methods of project development and pointed out the benefits of effective stakeholder involvement in ensuring better outcomes of large and small scale urban development and infrastructural projects (Elwood, 2004; Ghose, 2005; Healey, 1992, 1997, 2003; Innes, 2004; Innes and Booher, 2000; Swyngedouw, 2005). In the context of Indian planning also there is increased acknowledgement for the need of greater citizen involvement and broader stakeholder consultation to transform traditional top down practices into more inclusive ones (Coehlo et al, 2013; Corbridge et al, 2005; Hickey and Mohan 2005). The Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission launched in 2005, and the Smart Cities Mission launched in 2015, are all attempts to institutionalize this sentiment within India’s urban governance. However, it is evident from existing literature that involving multiple, often contending stakeholders, and negotiating/mediating their interests is not an easy task (Elwood, 2002; Ghose, 2005; Martin,2004; McCann, 2001; Roy, 2011; Swyngedouw, 2005). As Forester suggests, effective participation is “(E)asy to preach but difficult to practice” (2006:447). Especially in India, traditional top down approaches, market-centric development strategies, lack of trust towards authorities, multiplicity of stakeholders, corruption, lack of civic commitment to participate and act on one’s own behalf, all pose challenges for effective stakeholder involvement.

While in theory there is wide acknowledgment that poor management of stakeholder participation can be detrimental to project implementation, in practice, stakeholder involvement often remains limited in terms of their depth, breadth as well as time commitment (Coehlo et al, 2013; McCann, 2001; Miller and Lessard, 2001). In this paper, we want to highlight that effective stakeholder involvement that existing literature eludes to needs to be a thorough and long-drawn process, particularly for successful implementation and sustainability of public space projects. This is because governance, use, and appropriation of such spaces is diffused in the hands of multiple stakeholders and largely depends on development of a sense of ownership of the space and the rules/norms of the space, which can only develop through in-depth and continued stakeholder involvement. As such, we use a case study of the Luz Church Road redesigning project in Chennai to answer the following questions – Is it vital to engage with stakeholders beyond the project shaping or pre-award phase in public space development projects? If so, what kinds of strategies and approaches may be used to make such engagement effective for long term sustainability of public space projects? The Luz Church Road redesigning project in Chennai was primarily imagined by its initiators (a group of professional architects who also happened to be residents of the area) as an effort towards developing pedestrian friendly streets. Drawing from the experience of this partially successful and contestation-ridden public space planning effort for a seemingly socio-environmentally desirable goal, we suggest that stakeholder involvement should not be used as a one-time tool at the beginning, but rather should be thought of as an ongoing process of identifying/mapping, engaging, and anchoring the stakeholders in the project to secure long term sustainability of such projects. Drawing on existing theoretical work and our case study, we therefore propose a conceptual framework for an ideal lifecycle process of stakeholder management in public space planning.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Reinforcing effective stakeholder involvement

In the last few decades, the nature of urban development, planning/policy making, and project management has changed with a visible move from government to governance (Swyngedouw, 2005) raising interest in public-private collaborations, user or stakeholder involvement with specific attention to greater public participation, multi-party, multi-sector and multi-scalar co-operation etc (Elwood, 2002, 2004; Ghose, 2005; Martin, 2004; McCann 2001; Pattison, 2001). As such, Innes and Booher (2004) argue that meaningful participation must be perceived and operationalized as a collaborative process that engages a wide range of stakeholders from citizens to special interest groups, non-profit organizations, private, and public sectors. Agger (2012) further points out the need to categorize the notion of singular citizens or public, based on reasons of participation (or nonparticipation) and to tailor participatory processes accordingly. As such seeking broad-based participation seem imperative for effective stakeholder management. However, the work of a project planner/manager only begins with identifying all affected groups.

Just as the breadth of stakeholder involvement is important, so is its depth essential. Debate on most effective means and methodologies to achieve meaningful/in-depth participation is rampant (Agger and Löfgren, 2008; Healey, 1997; Hillier, 2003; Purcell, 2009; Roy, 2011). Understandably, there is no universally effective method of stakeholder involvement/engagement (Smith et al., 1997). While public consultations are commonly used means for seeking general approval from diverse stakeholders at the very beginning of planning/designing phase, scholars have pointed out how such consultations are often organized in the form of “exclusive enclaves” and/or “one-off (or a limited number of) consultative events” that displaces more “sustained processual engagement” (Coehlo et al, 2011). Taking examples like that of the consultation held by the Adyar Poonga Trust (working on eco-restoration of the Adyar Estuary in Chennai) Coehlo et al (2011) further elaborate how such consultations may be means of generating acceptance for top-down and/or already decided proposals. Even in case of well-intended and advertised public meetings, the most marginalized often remain absent. As such, these traditional methods need to be supplemented with alternative and context specific methods of stakeholder identification and engagement to broaden and deepen stakeholder management efforts.

Often, this discussion around effective citizen participation and stakeholder involvement remain focused on pre-planning phase of project development. For instance, in studying the implementation of large engineering projects, Miller and Lessard (2001) emphasize the importance of the ‘fuzzy front end’ of projects and the need to shape projects early on through effective interventions and dialogues with stakeholders. This focus on early planning phase might be partly because of time and resource constraints that limit continued investment into stakeholder involvement. And partly, this could be explained in terms of the assumption that if stakeholders are involved using a transparent, ‘fair process’ (Kim and Mauborgne, 2003) in the pre-award stages of a project then any risk of project failure is virtually eliminated post-award. However, we must remember that public spaces/infrastructures are ultimately for the public to appropriate. Despite efforts to gather and accommodate stakeholder concerns during planning, how successful specific projects become (in terms of being used/appropriated and maintained by the public as par planning purposes) depends on the extent the public develops a sense of ownership in the project. Agger et al (2016) describe how different user groups involved to different degrees and at different stages of the planning process of several public park and community garden projects in Copenhagen developed different levels of ownership and therefore were ready to take different levels of responsibility for these public spaces in post-construction phase. Authors described the process of community-based network development based on sense of ownership and responsibility as “anchoring”.

But how may stakeholder management processes develop such ownership? What sort of strategies may be useful? In the end, targeted efforts to explain the gains of creating synergies with the varied interests of the multiple stakeholder groups and developing mutual trust is essential (Agger, 2012) so they can work in partnership. While such communication should not be meant for coercing stakeholders to accept top-down plans/projects without questioning (Purcell, 2009, Roy, 2011), to get multiple publics to see value in a project, planners and/or project managers might need to use targeted information/education, customized language, and different degrees of coaxing and cajoling to appeal to their diverse interests. Approaching questions of appropriate strategies from a social movement and institutional theory perspective can be telling. Social movement theorists point out that the need for a large group of people – residents, vendors, designers and visitors – to all pull in the same direction necessitates an approach that collectivizes norm-building. This needs framing (Benford and Snow, 2000) an agenda to build greater collective support for a cause. A similar process of collective support or norm building seem relevant for developing ownership within multiple stakeholder involved public space projects.

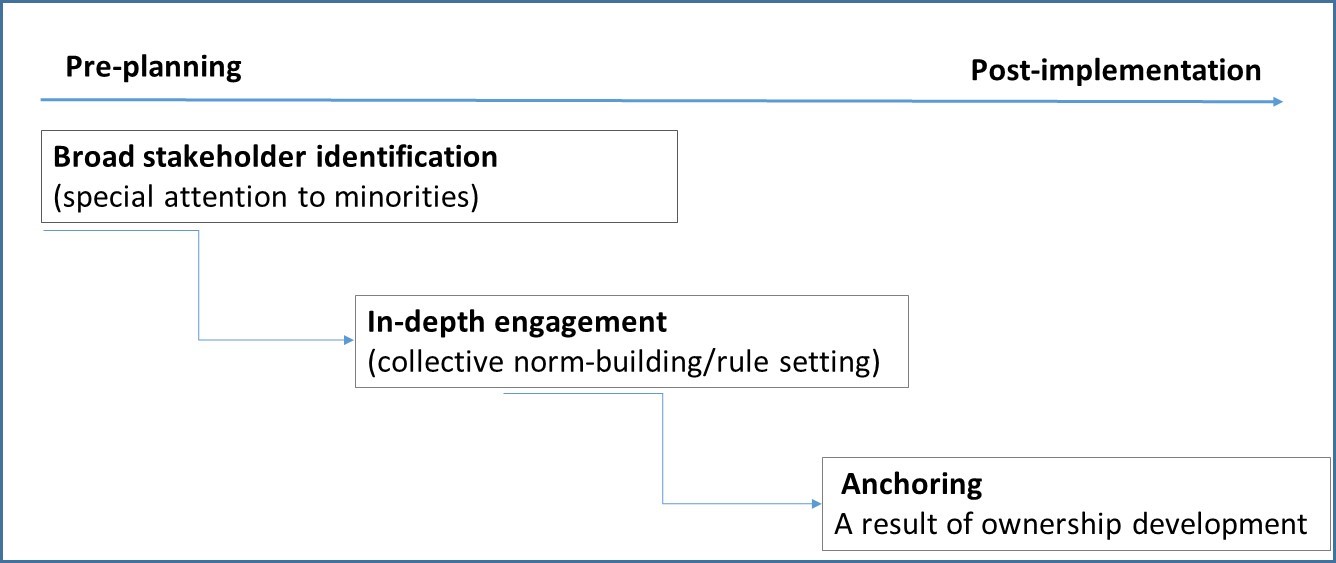

As far as specific strategies are concerned, institutional theorists suggest that institutions or ‘rules of the game’ (North, 1990) are reified or enforced through regulative, normative or cultural-cognitive means (Scott, 1995). Formal rules (regulative elements) coerce actors within a field to align themselves to existing institutions, informal norms incentivize actors to comply with rules that are perceived as legitimate out of fear of incurring social sanctions, and cognitive controls behaviorally align actors’ actions to prevailing values in the environment. Along similar lines, this paper shows how different strategies may be used to build the ‘rules of the game’, or more precisely the ‘rules of the space’ which in the case described involved developing a more pedestrian friendly space: in some cases, through coercive acts, in some cases by aligning the interests of the stakeholders along with the broader logic of the pedestrian friendly space etc. Drawing from the theoretical discussion and the following case study, we propose a broader conceptualization of an ideal lifecycle of stakeholder management process, which is not a one-time pre-planning period effort, but an effort towards processual engagement. This process begins with broad pre-planning stakeholder identification and involves in-depth engagement and ownership development throughout the project-implementation phase so it may result in post-implementation anchoring of the project in a network of local stakeholders ready to appropriate and take responsibility for the project (as shown in Figure 1a).

In the following section, we use the case study of the Luz Church Road redesigning in Chennai’s historical neighborhood of Mylapore to show how the various phases and actions described in Figure 1a are important for successful public space development and how shortcomings in any one may lead to problematic outcomes. Based on lessons learnt from the case study, we further refine the above framework with a nuanced understanding of stakeholder management process and strategies in our conclusion.

Figure 1a: Lifecycle process of stakeholder management

LUZ CHURCH ROAD CASE STUDY

We used a participant observation method for conducting our case study. The first author was one of the architects responsible for developing the Luz Church Road project and was involved in discussions with various stakeholders on the project. The data was collected primarily through the second and third authors helping the first author reflect on her experiences. This data was triangulated with information collected through archival research on newspaper articles and phone interviews with some of the key local stakeholders.

The Luz Church Project was part of an ambitious vision to make the streets of Chennai pedestrian friendly with universal access. One of the authors of this paper was part of this mission to guide the City Council and municipal agency to implement its strategy of increasing non-motorized transport and to shift the thinking away from an auto-centric approach to pedestrian and mobility focused approach in planning.

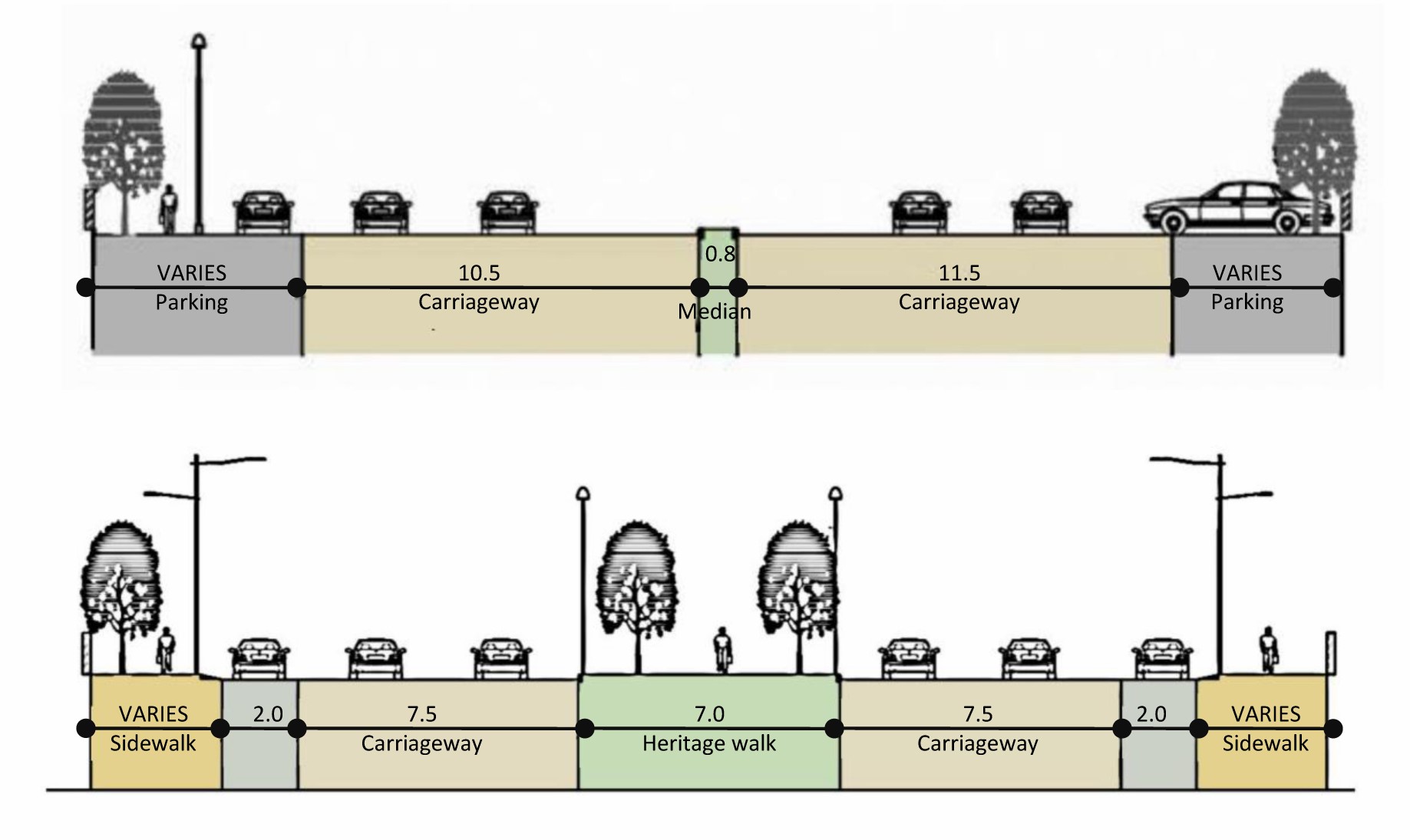

A specific 400m stretch of road in a historically important part of the city called Mylapore was targeted for the purpose (See Fig. 1). Besides a large temple and tank, there is a 500-year-old church, ‘Our lady of Light’ (Luz in Portugese) which lends its name to the street. While several buildings and institutions owe their roots to this neighbourhood not much attention has been given to the opportunity of attracting more visitors to the area by the city. About half the buildings on this street are historic buildings or places where important historic events have taken place. This particular stretch of the road was used as a one-way street despite being as wide as 24m. The roads leading in and out of this stretch were no more than two lanes or about 12m. The proponents saw an opportunity to create a central promenade with aspects of the area’s history and culture integrated in the design. This central median was envisaged as a walkway with streetscape elements like information signage, furniture, seating etc. The carriageway on both sides would still cater to 2 lanes of moving traffic on each side. Additionally, large sidewalks at both property edges were envisioned, which allocated space for walking, resting, street vendors and parking.

In the pre-planning stage itself the project proponents were convinced of its merit. They felt it was a foregone conclusion that others will fall in line. This was particularly because there was no plan to evict or displace anyone from the street.

Figure 1: Map of Mylapore showing streets around the case study area.

Figure 2: Diagram showing section of street – before and planned.

Figure 3: A before picture showing underutilized zone along the side of carriageway.

Pre-construction stakeholder identification:

As with any typical mixed-use street in India, particularly in the older parts of the city, there are multiple stakeholder groups. The type of commercial establishments range from high end textile store selling garments to the humble lady sitting right at their door step selling jasmine flowers. Other informal retail included food stalls, tender coconut vendors, fruit sellers and small kiosks selling assorted merchandise. These are all contending users of the public space.

With the intention of getting approval from the ‘public’ the City Corporation called for a public hearing. A single stage community participation workshop was conducted to share the idea with the citizens. This meeting was attended mostly by the hawkers and vendors, who were concerned that their livelihood would be affected by the implementation of the project. Once they were assured that no street vendors were going to be evicted, the project received seeming public support.

The media reports, announcing the public consultation, did not elicit any response, either positive or negative, from the newspaper-reading community in the initial stage. This absence of protest was understood as a general agreement to proceed. Rather than reaching out to those who did not attend the meeting the project team moved along with the implementation with the confidence that there were no major objections in regards to the proposed project.

The middle class in Indian cities is both skeptical of and disengaged with city level project announcements. It is only after seeing the project in execution that many questions were raised. Concerns about restricting traffic movement arose. One resident interviewed by the local paper raised his concern saying, ‘hardly anybody walks on these pavements. Why should we reduce the width of the road to make space for something that no one uses?’ Another person challenged the very idea of the heritage walk by questioning, ‘Who is going to walk in the middle of the road to look at history facts. Its dusty and so difficult to even get to?’ In fact, while the vendors were ok with the project since they were not being asked to move, the residents and middle class users felt that the design legitimized the place for such vendors. While some members of this same group are the customers, when asked to reimagine the street with place for all, they questioned the basis on which such ‘permanent’ provisions were being made for the vendor, thereby legitimizing the illegal status of their public space occupation.

The author received several messages from residents when progress on this work was carried in the media. One lady said, ‘these newly created footpaths will soon be home for a lot more vendors and we will be back to walking on the road’. The main central walkway was stopped midway during construction because of protests from the residents. They primarily thought of this project as one that would reduce traffic lanes and make way for space that they found difficult to imagine being used effectively. It did not matter that technically the original two lanes were being maintained albeit in a different alignment. This misunderstanding led to mass protests and eventually that part of the project was dropped.

In this case the stakeholders, who were absent from initial discussions proved to be the biggest critics of the project. A key component of the project could not be implemented, partly because of the nature of stakeholder identification exercise, which was restricted to a one time ‘town hall’ type of meeting. Furthermore, a passive stakeholder identification process that ignored a major user group and assumed their absence at the meeting as their support, proved to be detrimental to the successful implementation of the project. More on the ground meetings and active stakeholder identification which paid attention to all potential stakeholder and sought the opinion of those who were absent could have led to a different set of events around this project.

The inability to capture the imagination of the local resident group by offering a better visualization of the final outcome could have been one possible reason for the failure to implement the heritage walkway. For some the street was a livelihood and for others it was a space to move through between destinations. Perhaps offering a vision through ongoing communication and engagement that somehow rendered the street as a safe place for all would have been a more meaningful endeavor.

Figure 3: Image of Luz Church Road taken during construction of central walkway

Figure 4: Visualization of the heritage walkway

Figure 5: Newspaper report regarding the protest to drop Luz church project.

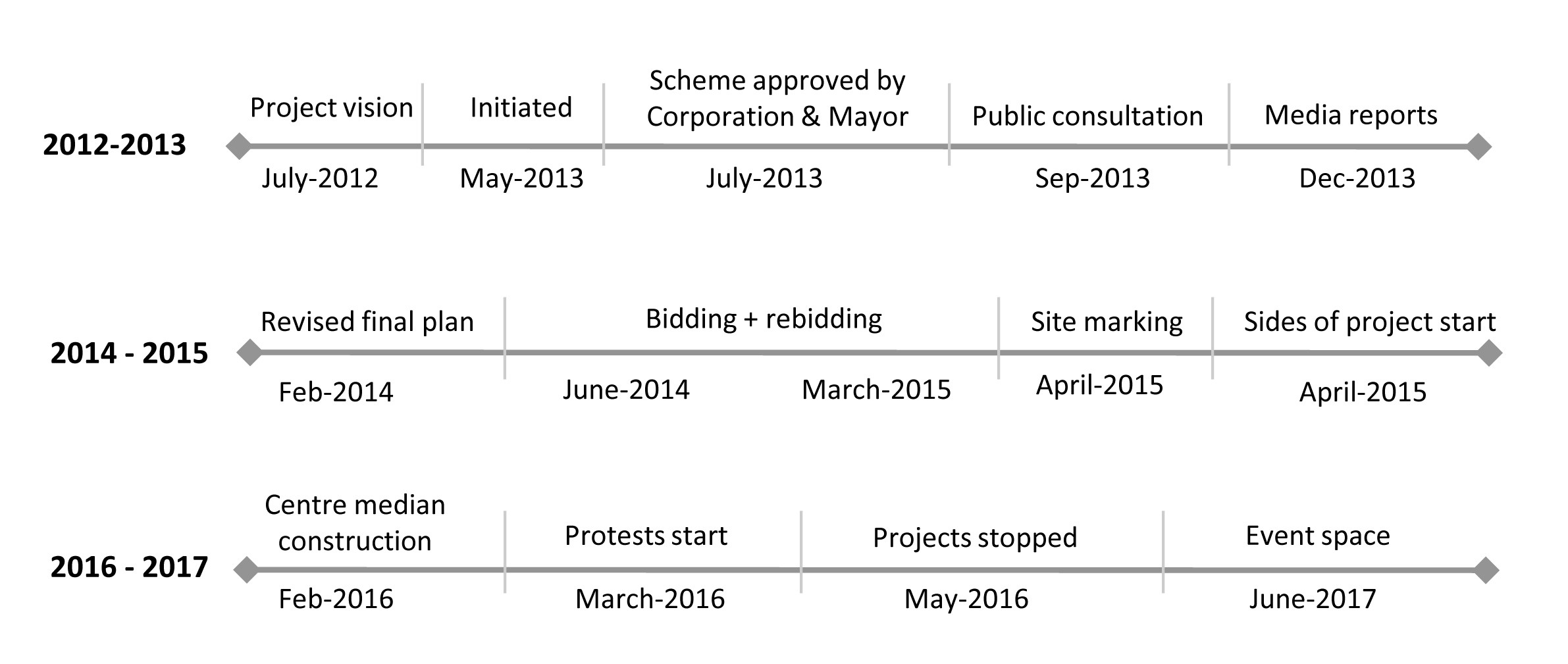

Figure 6: Project timeline

Stakeholder engagement: ongoing and innovative process

The form and character of each neighbourhood in the city evolves over decades. It is natural to expect resistance to projects that may modify the urban experience. Once the project had cleared the initial stages it was assumed that implementation would result in a walkable street. However, creating the physical space was not adequate. In the absence of strict enforcement on protecting these footpaths for use by pedestrians, it falls upon the stakeholders on the street to participate in the implementation of the idea. Luz church road has its share of colorful actors who contributed to the ‘placemaking’. One such character was the tender coconut seller, who occupied the street corner near the famous church had been a permanent fixture for over 10 years. A wholly nutritious and inexpensive beverage, its hard to beat the positive effects of tender coconut water in summer. The effect of this on public space is however, another story. There was a complete economy that revolved around the tender coconut sales wherein the street corner functioned as a mini wholesale market to unload, stock and distribute the coconuts. Several pushcarts, which are parked overnight on the footpath, sold these in various locations.

While there was a trust deficit in the beginning of the project, it became clear to the coconut seller that the sidewalks were going to be implemented. The space occupied by the vendor rendered the footpath project itself a wasted effort. After repeatedly pointing out that he needs to restrict himself to a particular zone he cooperated. In fact, patrons of the shop benefitted from the benches and seating provided near the pushcart on the newly created footpath. Traditional communication strategies were ineffective in sharing the project intent. Rather, chalk markings drawn on the street were helpful to visualize the benefits of creating and maintaining space for pedestrians. Repeated and innovative engagements was necessary in order to build an understanding as to how the project was not a threat to his interest, but in turn provided easy access and a place for his potential customers to sit and take a break. This kind of sustained interaction/communication is rarely envisioned at the start of the project. However, there is no alternative to this approach of processual engagement for long term sustainability of these types of projects.

Figure 7: Coconut seller during the construction stage

While the coconut seller and a few other vendors were able to see the benefit of the pedestrian project, some of the more permanent stores were habitual ‘encroachers’ of the space in front of their shops. A fast food restaurant, within 50m of the coconut seller was one such example. The store sign, which obstructed the sidewalk was removed with much difficulty. A reluctant participant of the project, they did not care for anything beyond the customers being able to enter and exit the store. In order to remove the obstructing sign itself, it needed a visit from the Deputy Commissioner of the Municipal Corporation.

Figure 8: Before and after of sidewalk next to the fast food restaurant.

The absence of a sense of community among the retail owners of ‘Luz Church Road’ is perhaps one reason for the disinterest in the project. However, a small community event caused a change of heart in the restaurant owner. The space adjacent to their store hosted an event to promote traditional games. This small event brought about 50 people to the footpath, but it was enough to establish the role that public space can play in creating a lively environment. The same stakeholder who had to be cajoled to remove the signage was now an active participant in providing support for the event. Creative strategies of engagement helped develop a sense of ownership and a willingness to maintain the public space within this restaurant owner leading to anchoring as described in Fig 1. Where such efforts were not made, the physical space alone failed to transform the public space as imagined through the pedestrian-friendly re-designing effort.

Figure 9: Widened footpath as event space.

Not every story on the street had a happy ending. The idly (a rice pancake) vending stall was owned by a politically connected street vendor who was an occupant of the space for several years. The same strategies employed to deal with the coconut seller were used to coax this vendor to use a defined space of the street and leave a pathway for pedestrians. While he remained polite and even seemed helpful, there was no interest or incentive for him to change his ways. The customers of the stall were loyal and couldn’t care for the need of pedestrians. In fact, one of them said’ there is so much space on the road, why can’t they walk there and let us eat our food in peace’. Using pressure from the commissioner’s office proved ineffective as a counter phone call from the ruling political party member was enough to annul the directive. The impunity with which this stakeholder laid claim to what was clearly common property shows that there was no fear of consequence. The middle-class customers saw greater value in the sale of inexpensive food rather than safe walking space.

DISCUSSION

It is evident from the incidents described in the case-study that parts of the project that succeeded were those where stakeholder engagement was continuous and innovative with attention to developing a sense of ownership. In line with the approach suggested in Figure 1a, the stakeholder identification process was careful to include citizens, particularly those who are normally marginalized, into the planning process. As such the interests of the street vendors, who are often most vulnerable to top-down project planning were protected from the conceptual stage itself. However, the stakeholders, specifically the middle-class residents, who one might assume would be supportive, given the project intent, were largely absent and silent during the consultative process. Later during execution, this silent majority posed serious threat to key elements of the project. Vendors/shopkeepers who were included in early consultations also posed threat to the successful implementation of the project by refusing to comply by the pedestrian-friendly norm of the newly designed public space. In some cases, the project execution team could solve the challenges that surfaced by coaxing, cajoling, and using innovating methods of engagement with contending stakeholders. In other cases, the challenges necessitated a re-course to re-design project parts, while in some cases the project team had to embrace conflicting views that emerged and surrender parts of the original design to evolving stakeholder responses.

In this case, the project team acted as institutional entrepreneurs do (Fligstein, 1997) to create a set of rules, norms and values around the public space at Luz Church Road to enable its sustainable use. The dominant institutional logics (Friedland and Alford, 1991) that they proposed essentially spoke to the advantages of maintaining pedestrian-friendly spaces which would lead to the elimination of urban ills such as traffic congestion, air pollution, the inability to walk around cities, lack of social spaces and so on. In some cases, this logic was instilled through developing a sense of value for pedestrian-friendly behavioral norms. In some cases, this was done by emphasizing the notion that economic activities (such as roadside sales by hawkers and street vendors) could also flourish in such a setting.

While some stakeholders bought into these logics, others resisted. In the case of the owner of the fast food joint who was using the sidewalk to park his food vehicles as opposed to keeping it obstacle free for pedestrian movement, recourse to formal regulations helped. A visit from the Deputy Commissioner of Chennai Corporation to remind the owner of his legal obligations led to speedy clearance of the sidewalk. However, in several cases such a strategy was not possible. The coconut seller for instance was an unregistered agent, operating out of a cart on the roadside. In the beginning, he resisted providing space on the sidewalk to pedestrians. However, he soon recognized the economic benefits he stood to gain if he allowed chairs to be placed in the sidewalk for elderly passers-by, who were then more likely to buy coconut-water from him and enjoy it while sitting down. As a result, a set of self-enforcing norms were created where the pedestrianization of the Luz Church Road space incentivized the coconut seller to keep the sidewalk obstacle-free in order to boost business. The pedestrians further legitimized this use of the public space by relaxing in the benches provided for them, enjoying coconut water while they sat.

In some cases, contradictory logics brought in by stakeholders could not be resolved and the logic of the space had to be changed. In the case of the idly-shop in front of the bank, the vendor refused to restrict his operations to a portion of the sidewalk and to keep his surroundings clean. As a result, the area adjoining his establishment was no longer pedestrian friendly. The coercive approach of bringing in the city’s deputy commissioner failed as this vendor had deep political connections with the ruling party in the state of Tamil Nadu. Furthermore, the vendor did not buy into the logics espoused by the project proponents and did not see any value in conforming to these ideas. Other stakeholders such as the residents, pedestrians and customers of his shop also did not exert enough normative pressure to get him to change his approach to selling idlys on the street.

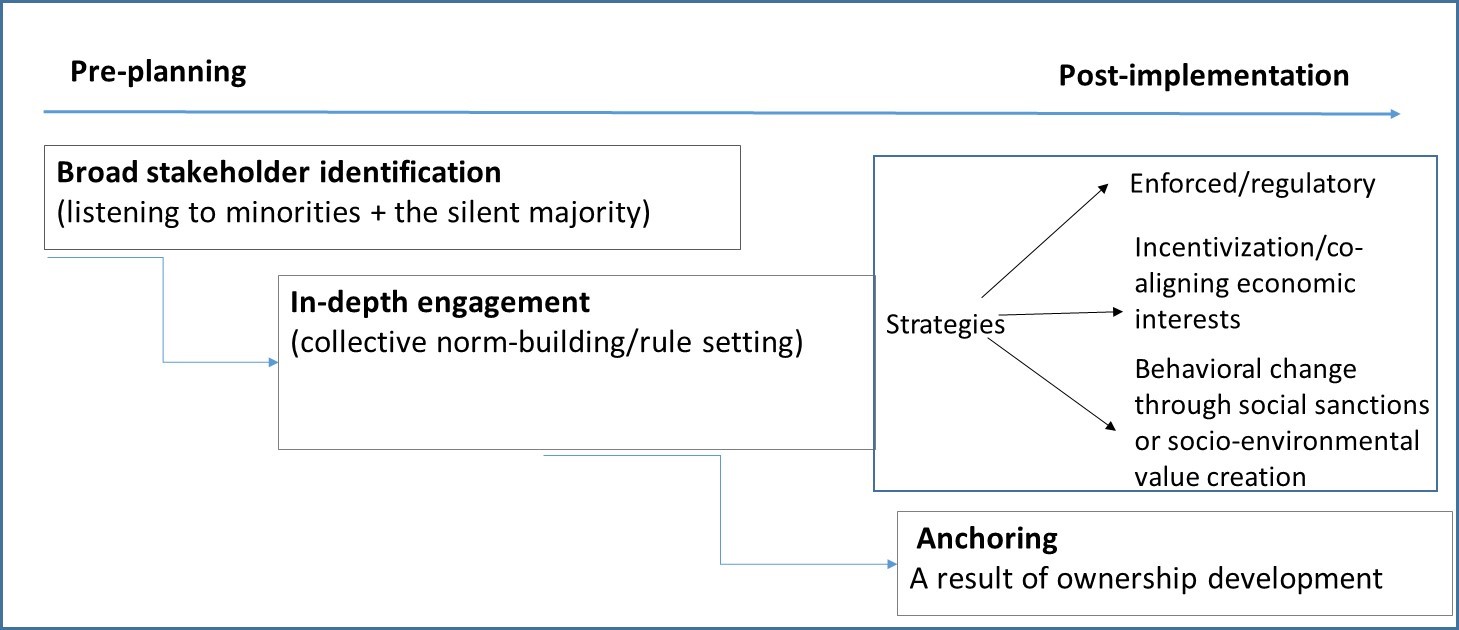

These anecdotes indicate that unlike physical infrastructure projects such as roads or power plants where project governance is clearly vested in the hands of select players (the concessionaire in the case of a toll road for instance), the governance of public spaces is far more diffuse. While the local municipal authority – the corporation of Chennai in this case was responsible for contracting out the work, the project design and more importantly the rules of the space were conceptualized and operationalized by a diverse group of citizens. Developing shared norms of public space use in such situations is fraught with complexity as stakeholders often will need to overcome trust deficiencies that exist between one another. In cases where stakeholders could develop such swift trust, or in cases where interests mutually aligned, a self-governing set of norms for using the space were both created and repeatedly enacted. Where this was not the case, stakeholder views came into conflict, and a dominant view carried the day, often to the detriment of the overall vision of the project. Drawing on this experience, we further refine the proposed framework representing the lifecycle process of stakeholder management with two nuances: first one involves drawing attention to silent majority along with the minorities/marginalized stakeholders and second one is related to strategic suggestions for ownership development (Fig 1b).

Figure 1b: Lifecycle process of stakeholder management with strategy suggestions

Overall, while the Luz Church project team was able to integrate diverse views into the design of the project through consultative discussions they were in certain cases unable to create the collective, shared vision that would foster ownership development/anchoring and therefore help govern the project in line with its stated intentions. Despite these obstacles, it may be premature to consign this project as a failure. From a co-design perspective, the current case may be looked upon as an iteration based on an initial prototype, through which the views of users are better understood, that may then lead to another prototype that may capture user needs better (Melles et al, 2011).

This paper set out to understand whether the necessity of managing stakeholders through and beyond project execution existed. The answer is a resounding yes, particularly in cases such as the design of urban public spaces where the stakeholder network is large and diffused. We also suggest that urban designers may need to align their strategies with those successfully enacted by institutional entrepreneurs or social movement leaders, who attempt to frame a shared agenda, and create collectively legitimized and socially enforceable norms for the use of public spaces to make these projects work.

References:

Agger, A. (2012). Towards tailor-made participation: how to involve different types of citizens in participatory governance. Town Planning Review, 83 (1), 29-45.

Agger, A., & Löfgren, K. (2008). Democratic assessment of collaborative planning processes. Planning Theory, 7:145–164.

Agger, A., Roy, P., & Leonardsen, Ø. (2016). Sustaining area-based initiatives by developing appropriate “anchors”: the role of social capital. Planning Theory & Practice, 17(3), 325-343.

Arnstein, S.R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224.

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual review of sociology, 26(1), 611-639.

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual review of sociology, 26(1), 611-639.

Bourne, L. & Walker, D. H. T. (2005). Visualising and mapping stakeholder influence. Management Decision, 43(5), 649-660.

Coelho, K., Kamath, L., & Vijayabaskar M. (2011). Infrastructures of Consent: Interrogating Citizen Participation mandates in Indian urban governance, IDS Working Paper 362, Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex Brighton BN1 9RE UK.

Coelho, K., Kamath, L., & Vijayabaskar M. (2013) (Eds) Participolis: Consent and contention in neoliberal India. Taylor & Francis Group.

Corbridge, S., Williams, G., Srivastava, M., and Verone, R. (2005). Seeing the State: Governance and governmentality in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elwood, S. (2002). Neighborhood revitalization through ‘collaboration’: Assessing the implications of neoliberal urban policy at the grassroots. GeoJournal 58, 121–130.

Elwood, S. (2004). Partnerships and participation: Reconfiguring urban governance in different state contexts. Urban Geography, 25, 755–770.

Fligstein, Neil. “Social skill and institutional theory.” American behavioral scientist 40, no. 4 (1997): 397-405.

Fligstein, Neil. “Social skill and institutional theory.” American behavioral scientist 40, no. 4 (1997): 397-405.

Forester, J. (2006). Making participation work when interests conflict: moving from facilitating dialogue and moderating debate to mediating negotiations. Journal of the American Planning Association, 72(4), 447-456.

Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions.

Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions.

Ghose, R. (2005). The complexities of citizen participation through collaborative governance. Space and Polity, 9, 61–75.

Healey, P. (1992). Planning through debate. Town Planning Review, 63(2), 143–162.

Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies. London: Palgrave.

Healey, P. (2003). Collaborative planning in perspective. Planning Theory, 2(2),101–123.

Hickey, S. & Mohan, G. (2005) Relocating participation within a radical politics of development. Development and Change, 36(2), 237-62.

Hillier, J. (2003). ‘Agon’izing over concensus: Why Habermaisan ideals cannot be ’real’. Planning Theory, 2(1), 37–59.

Innes, J. (1996). Planning through consensus building: A new view of comprehensive planning ideal. Journal of American Planning Association, 62(4), 460–472.

Innes, J. (2004). Consensus building: Clarifications for the critics. Planning Theory, 3(1), 5–20.

Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2004). Reframing Public Participation: Strategies for the 21st Century. Planning Theory and Practice 5(4), 419-436.

Innes, J., & Booher, D. E. (2000). Public participation in planning: New strategies for the 21st century. In Annual conference of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning, November 2–5, University of California at Berkeley, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, 1–39.

Johnson, G. & Scholes, K. (1993). Exploring Corporate Strategy, 3rd edn., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2003). Fair process: Managing in the knowledge economy. Harvard Business Review, 81(1), 127-136.

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2003). Fair process: Managing in the knowledge economy. Harvard Business Review, 81(1), 127-136.

Martin, D. G. (2004). Non-profit foundations and grassroots organizing: Reshaping urban governance. Professional Geographer, 56(3), 394–405.

McAdam, D., & Scott, W. R. (2005). Organizations and movements. Social movements and organization theory, 4-40.

McAdam, D., & Scott, W. R. (2005). Organizations and movements. Social movements and organization theory, 4-40.

McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (1996). Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge University Press.

McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (1996). Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge University Press.

McCann, E. (2001). Collaborative visioning or urban planning as therapy: The politics of public–private policy making. Professional Geographer, 53(2), 207–218.

Melles, G., de Vere, I., & Misic, V. (2011). Socially responsible design: thinking beyond the triple bottom line to socially responsive and sustainable product design. CoDesign, 7(3-4), 143-154.

Melles, G., de Vere, I., & Misic, V. (2011). Socially responsible design: thinking beyond the triple bottom line to socially responsive and sustainable product design. CoDesign, 7(3-4), 143-154.

Miller, R., & Lessard, D. (2001). Understanding and managing risks in large engineering projects. International Journal of Project Management, 19(8), 437-443.

Miller, R., & Lessard, D. (2001). Understanding and managing risks in large engineering projects. International Journal of Project Management, 19(8), 437-443.

movements? Planning Theory, 8, 140–165.

Newcombe, R. (2003). From client to project stakeholders: a stakeholder mapping approach. Construction Management and Economics, 21(8), 841-848.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge university press.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge university press.

Olander, S. (2007). Stakeholder impact analysis in construction project management. Construction Management and Economics 25(3), 277–287.

Olander, S. & Landin, A. (2005). Evaluation of stakeholder influence in the Implementation of construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 23(4), 321-328.

Pattison, G. (2001). The role of participants in producing regional planning guidance in England. Planning Practice and Research, 16(3–4), 349–360.

Purcell, M. (2009). Resisting neoliberalization: Communicative planning or counterhegemonic

Roy, P. (2015). Collaborative planning – A neoliberal strategy? A study of the Atlanta BeltLine. Cities, 43, 59–68.

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations (Vol. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations (Vol. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Swyngedouw, E. (2005).

Governance innovation and the citizen: The Janus face of

governance-beyond-the-state. Urban

Studies, 42(11), 1–16.