Stakeholder management in public space projects-2019

Introduction

India is poised to make significant investments in cities through various programs like the Smart cities mission, urban renewal scheme, HRIDAY etc. There are usual challenges in implementing a lot of these projects as one would expect from an emerging economy – lack of capacity in municipal agencies, excessive population with limited resources. There are always diverse demands on limited public funds often combined with technical complexity of dealing with legacy infrastructure.

In addition to infrastructure projects that will deliver energy, water supply, sanitation services etc, these urban renewal schemes envisage the development of public spaces, where by definition, multiple stakeholder groups will be involved. Public space projects often have mixed outcomes due to the various factors mentioned above. Sometimes there is a significant gap between the way a space is envisioned and how it is actually utilized. Many times the diverse demands on public space make it impossible to create single use type of spaces. Lastly maintaining and perpetuating the use of these spaces remain challenging due to a combination of factors, such as, limited funds, lack of citizen engagement, and absence of any clear owner.

Historically the commons were governed by rules within the community. The use was regulated by traditions and managed by established yet unwritten norms. Some examples are the street markets in Ahmedabad, where the same space alternates between multiple vendors and governed by their rules of operation. Likewise, use of streets during festival times, were moderated by the religious calendar, where people changed the retail usage to accommodate requirements during festivals. These demonstrate traditional and accepted norms amongst users of these public spaces.

With urbanization, completely different sets of people are forced to live in dynamic groups and the network of actors which create and manage shared spaces have to be seen in a completely different context. This establishes the importance of why a study of the roles of various players in public space creation is critical. This can leave us some insights into what we need to consider before embarking on such projects.

Theoretical Background

Public space projects are multiple stakeholder driven (Selvaraj et al, 2017, Roy, 2015). While traditionally public spaces were planned top-down primarily by state agencies and implemented by state agency chosen organizations in accordance to the desired goals of the former (Healey, 2003; Innes, 2004), planning principles have evolved to aspire for more participatory processes – processes involving multiple public and private actors, in other words all affected stakeholders, to play a critical role in planning cities in general and public spaces/projects in particular (Elwood, 2002, 2004; Coehlo et al, 2013.).

However, as a reflection of two case studies will show, multiple stakeholders are involved not alone at the planning stage, but also during the design/implementation phase, and the appropriation/maintenance phase. That is new stakeholders may emerge and transform the project network or governance structure at later stages. As such while reflecting on area-based renewal projects Agger et al, describe how such processes involve different kinds of organizational networks, primarily to contribute to the early stages of planning where problems and solutions are contemplated, while the network may transform as new actors emerge during implementation or even after completion of the projects (2016).

As planning theory and practice literature recognize the need for more collaborative and multi-stakeholder driven processes, this literature along with construction management, organizational studies, business management etc., also recognize the complexity involved in navigating the diverse interests/powers/roles of these stakeholders within such networks (Forester, 2006; Caniato, et al, 2014; Bodin et al, 2006; Newcombe, 2003). Since such “…network structures can either enhance or inhibit stakeholder interactions and influence project performance” (Caniato et al, 2014), effective stakeholder management is an essential part of contemporary planning and development processes, not in the least in community-centric projects such as designing and building public spaces. And someone (or a collective) who is “capable and willing to hold the diverse actors within networks together and make them work together” ideally needs to take on this job of stakeholder management as a ‘network manager’ (Holman & Rydin, 2013).

In cases where public administrators/planners lead such multi-stakeholder driven public space projects they are expected to play the role of the “network manager”. However, as more and more public space projects are conceived, initiated, and often lead by partnerships between multiple public and private parties, who takes up the role of the “network manager” or “integrator” as we call them in this paper within such a network becomes critical. For it is the nature of the integrator (power, interest, legitimacy) that can largely influence the nature of the network to be either largely centralized or collaborative. In turn this has influence on the strategies used for network management.

For instance, a centralized integrator is often characterized by a lot of power and high legitimacy that allows this integrator to effectively coordinate between multiple stakeholders to work together efficiently and if required direct the project in the direction of their choice despite multiple and even contending stakeholder interests. This sort of network may be multi-stakeholder driven, but represents hierarchical or centralized network management that can threaten the very purpose of multi-stakeholder driven projects to foster democratic processes/outcomes.

In absence of such a centralized integrator, there is scope for interested and responsible network participants to take up the role of an integrator. However, they might not enjoy the sort of power and legitimacy as the centralized integrators and hence have to rely more on softer forms of network management strategies or rely on powerful stakeholders to manage stakeholder interests/demands.

The need for network management or stakeholder management has been highlighted time and again (Newcombe, 2003). However, there are still gaps in our understanding of how organizational structures or project governance structures can help manage variety of stakeholder interests leading to successful completion of public space projects. Therefore, this paper intends to focus on this network or project governance structure and pose the following research question

1. How do project governance networks evolve over time in public space projects?

2.What are the different strategies that project integrators use in their effort manage stakeholder diversity and resolve conflicts?

3.What is the relation between the nature of the integrator and the network with respect to the stakeholder management strategies?

The two cases we present show different models-one of a park space where an architecture firm responsible primarily for design and implementation takes up the role of an integrator and operates within a comparatively more collaborative, somewhat diffused network of stakeholders. The other is a temple where the principal donor and the religious heads play the role of the integrator within a centralized stakeholder network. Both projects were completed successfully, but using different stakeholder management strategies.

Case Study 1 – Inclusive Play space

The first case study under consideration is an Inclusive Park, designed for children with and without disabilities. The inclusive park was initiated by the ‘Disability Rights Alliance’ a group of citizens focussed on creating accessible public spaces. The architecture firm, Cityworks , conceptualized the project and took it to the Government municipal body as a proposal. During design, bidding and execution the architects played the role of problem solving at every stage, often taking roles not traditionally done by design firms.

Some examples of such activities include conflict resolution when local residents raised concerns on the design, fund raising through private donors for special equipments and finding corporate sponsorship to maintain the park. The local political representatives wanted to be involved and Chennai Smart City Ltd, which was funding the project had project managers, who remained only on paper as coordinators. Within a few weeks into the project the design firm realized that no single agency was anchoring the project. This led to unresolved issues and no clear decision making. In light of the firm’s commitment to green and inclusive public spaces, this actor proactively took the leadership/integrator role, and negotiated between different interests to ensure that the project was completed on time.

In the initial stages of the project, a workshop was conducted by the design team to collect inputs from teachers, and parents of children with disabilities. These were translated into plans, which were cleared by the municipal authorities easily as they had no specific domain expertise in the area of disabled friendly design. However, the design team felt it was critical to get the support of the members of the Disability Rights Alliance (DRA), and organised a project walk through. DRA is a loosely structured group that champions the cause of persons with disabilities in the design and maintenance of public spaces. So naturally, given the range of disabilities it is not possible to make a space that suits the requirement of all. Some parents wanted more wheelchair accessible play equipment, others felt that the visually challenged had less items to engage with. There were also some comments about the inadequate facilities for autistic children. These various comments and requirements had to be patiently addressed. A partner organization, Kilikili, which champions play space design was roped in to mediate and bring consensus by explaining the constraints of space, budget etc and pointing out that this park was the first of many such playspaces planned in the city. Their feedback would be suitably addressed in the next projects.

Figure1: Members of DRA inspecting the park during construction.

In another instance, once the construction started, there was protest from persons from the local community, who were using the space to play badminton. They complained to the local politician (MLA) who was a very well intentioned person looking to upgrade the public spaces in his constituency. According to this group of community members, the space was used continuously for the last 50 years as a badminton play area. When it was explained that an inclusive park was envisaged here they wanted the design to be modified to retain the badminton court at the center. They suggested that the children’s play equipments could to be placed on the periphery around the court. In fact, they prepared a drawing and came to the MLA’s office with an alternate proposal. As designers, the author’s team and the parks department officials were called to discuss this revised proposal. A meeting was set up at the park itself. During this time, the voices of the residents were heard and also the larger purpose and intent of the park was explained. The design of the open play was extended to create a larger space for them to play badminton. But it was retained in one corner only as per the original design. It was also decided to create a separate gym in an adjacent area in order to minimise the need for adults to enter the play space.

Only after the requests were addressed, did the members allow the contractor to proceed with the construction. Even though their requirements were not fully met, the community realised the wider significance in creating a play space for a unique user group.

Figure2: The extended multi play open court at the rear end of the park

Figure3: Before and after pictures of the park.

As some of the issues were addressed during construction, the bigger challenges emerged post inauguration. Within a month of the Chief Minister’s ceremonial opening of the park, the team observed the problems with the way people were using the space. Teenagers and adults were found using the play equipment which was meant for children. Several equipments broke in the initial weeks of the park’s opening. It became clear that there needed to be an intervention to educate on how the space may be used. The core group decided to reach out to the local community and used social media to ask for volunteers. Slowly a few members came together to take care of the park and protect it from miscreants. Social media was critical in creating a virtual community. By including the park department engineer there was greater legitimacy to this group. A few members became champions of the space and between themselves made sure that some persons were present during the peak hours of usage. This experiment of having volunteers be present in the park is unprecedented in Chennai and the group was given the responsibility of framing the rules of usage and timing.

Figure4: Damaged play equipments after few months of inaugurating park.

Figure 5: Members from the local community with their volunteer badge.

Anchoring this project, the design consultants were faced with multiple needs to meet with the stakeholders to move the project forward. Firstly during the design stage, the stakeholders were those who would be potential beneficiaries of the project. Engagement with them was done to make them feel included, while moderating the expectations given the limited space and budget for the project. This was handled by one of the partners who was operating in the NGO space. She coordinated with the other disability groups to get their inputs and spoke on their behalf with the principal consultant.

The second type of interface with stakeholders was to placate those who felt their space was being taken over despite the long history of using the space. For this aspect the team leaned on the local politician to mediate. Concessions in design were made and alternate facility, albeit much smaller, were created to deal with the expectation of the local community of erstwhile users. There was of course, the technical side of the projects which involved all the procurement, engineering and site related issues for which the design team took ownership. Despite there being a project manager on board, the way in which system is set up, the responsibility of getting the project executed lay with the designer.

The most important stakeholder group emerged after the completion of the project. Since this was a one of a kind park, it attracted a lot of usage from people in the area. Media coverage ensured that people knew about it and came to see the place. People from the neighbourhoods close by also visited regularly. Low income neighbourhoods have no planned open spaces and definitely none with the level of elements created in this park. A lot of misuse of the equipment caused immense distress to those who worked hard to create the park. In India people have a relationship with public realm where it is difficult to bring the sensitivity that this space belongs for common use and all are responsible to take care of it. A community meeting was called for and a local newspaper wrote asking for community members to be volunteers for the park. This is not a common practice in Chennai but the concept resonated with citizens who felt that they should not allow the infrastructure created to fall apart because of apathy.

Figure 6: Local newspaper article, calling community members to be volunteers for park.

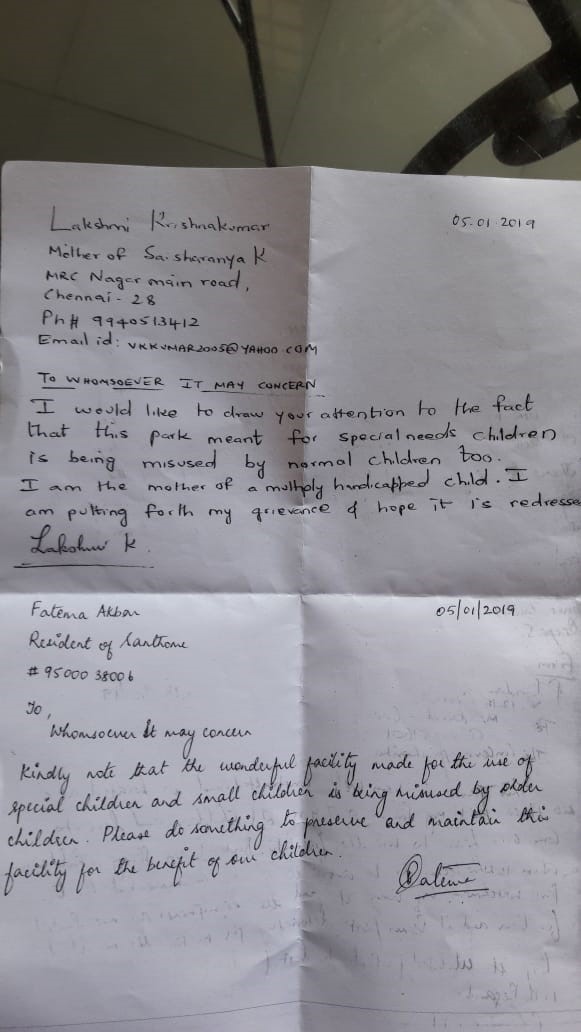

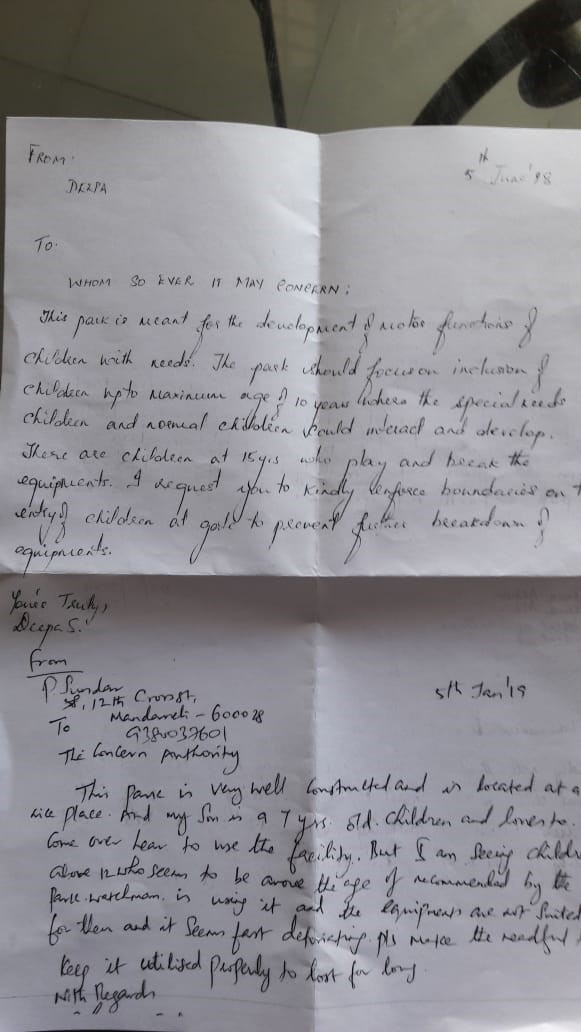

The design consultants also approached corporate sponsors to fund the maintenance, which they were able to get. But more than paying for security and housekeeping the real challenge remained in setting the rules for the park. Parents of children with special needs petitioned the designers to include signage that clearly stated who the park was intended for. There was also much debate on the timings – whether to keep some hours exclusively for children with disabilities. While the intention of the park was for inclusive play, the popularity of the place brought so many people that it became difficult to manage. Between the members of the core group and some volunteers, the schedule of the park was drawn up and incorporated as signage in the park on a trial basis. The team agreed that this will be reviewed after a month.

Figure 7: Petitions received from parents.

An important outcome of this project has been the manner of handling various stakeholders with agility and with the design team not restricting themselves to their defined scope but rather taking ownership and acting as anchor for the overall outcome of the space. Overall, this approach has led to successful use of the space for the targeted group. There will, no doubt, be challenges in maintaining the space in the long term. But engaging with various groups at each stage and finally creating a viable organization framework may lead to a sustainable set up for the Inclusive park.

Case Study 2 – Restoration of Sri Kamakshi Amman Temple

The second case study involves the renovation and rehabilitation of a historic temple with the principal structure dating to the 14th Century. The temple itself was a very significant place of worship for millions of Hindus. The project was funded as a major private donation. Given the historic nature of the temple and the significance in the minds of devotees the restoration process needed to tackle issues beyond technical challenges. Various experts ranging from archaeologists, epigraphists and historians to sthapatis (temple architects) engineers and priests were to be consulted to ensure that the outcome satisfied the maximum parameters. Expectations of HR & CE, the government body in charge of the temple and trustees of the temple were also to be managed for the successful outcome of the project.

Under the expert guidance of the principal donor a core group of 3 members was constituted as anchor for the project. Each person (including the first author) was assigned the task of managing one set of stakeholders while coming together and resolving amongst themselves the challenges that were faced during planning and construction. Even though this was a relatively small project compared to large infrastructure projects, the nuances around sequencing of the work, technology used, material selection, managing stakeholders etc, all had to be mindful of the traditions of the temple during the implementation phase.

The key stakeholder was the spiritual head of the temple. He interviewed the principal architect before permitting the work to proceed. The design direction was clear – flexibility to the project team on the outer periphery of the temple and strictly following the temple traditions in the sanctum sanctorum. In the aspects and spaces that did not fall under these two distinct categories, it was decided that some negotiation between the parties could result in joint decision making. The temple also had trustees, who were well regarded public figures in Chennai. One of the members was assigned to go and meet these people individually and appraise them of the project and approach and also to seek their advice. This ensured that they did not feel their position was disrespected.

During the course of fifteen months, which was the duration of the project, various stakeholders had to be managed. One such important group in significant historic buildings is the media. It is natural that there would be a lot of media attention on temple restoration projects. Several poorly executed projects have cast a spotlight on the work of restoration in historic structures. Unfortunately, in many cases centuries old sculptures have been disfigured. During the time of the project under discussion, there was a case pending in high court of Tamil Nadu seeking to halt all the temple renovation projects stating that they were flouting norms and best practices. The study project, while not being specifically targeted, was caught in this list of projects. An expert committee, appointed by the High court sent a senior archeologist to assess the work. This person had some observations on the approach. He also had the power to have been able to stop or delay the progress. However, the spiritual head, Sri Sankaracharya, reached out to the expert and explained the context of the work. Given that this is a living temple (as opposed to a monument – where different set of rules apply) , certain modifications should be acceptable to suit the convenience of ritual practice. The archeologist, being a devotee of the temple, was able to understand the implications of delaying the project through unnecessary court interventions and the team was able to negotiate a mutually acceptable solution that kept the spirit of preservation intact while allowing for the modifications to be made.

Given that the temple is a public space and continually open for worship during the course of the project, the team faced constant questions, complaints and suggestions from the general public. In one specific instance, a modern addition to one of the shrines was planned to be demolished to create a stone pavilion, which was in line with the historic structure. A visitor, who was shocked to see the demolition work, complained to the temple about it and promised to return the next day to document, what he felt was incorrect process being followed. This was a member of the general public and he threatened to go to the media with photographs high lighting the demolition. The project team acted quickly and completed the demolition over night, cleared the area of debris and stacked the new ornamental columns in plain sight. This established the intent of the temple to replace an asynchronous structure with something more compatible. The nature of modification throughout the temple was so large and varied, that it was not possible to create and maintain drawings and views to convince every member of the public about the design intent.

Figure 8: A modern addition that was demolished and replaced with a stone pavilion.

One important element added during the design stage was a queue system for the pilgrims to wait in line. The temporary arrangement that existed in the temple was poorly built and had inadequate facilities for devotees. The principal designer took a bold decision to create a pillared walkway that was placed adjoining to the main temple wall. In order to preempt questions about the permanent nature of this structure, the design team reached out to all the stakeholders to get their buy in for this significant addition.

Figure 9: Before and after pictures of the walkway created for the pilgrims to wait in queue.

Certain temple historians, who were known to be influencers, were also individually met and apprised on the plan to create this new structure. Most importantly, the spiritual head, who was the power center in the project fully supported the idea to facilitate a convenience for devotees and was willing to take the risk of some voices which may object to creating a new permanent structure so close to the existing temple wall. With the buy in and support of all, the team proceeded with the work and today it is a much admired facility, which other temple trustees are visiting to emulate in their projects.

Discussion

Both cases highlight the idea that public space projects are replete with a variety of stakeholders who attempt to influence, and in some case derail the project. One aspect of similarity between the two cases is that stakeholders materialize across phases of the project. While some are evident during the planning phases, others appear during the construction operations phases – users of the park for instance, or devotees to the temple. While stakeholders who are identified early on can have their wishes accommodated through changes in design, this becomes progressively more difficult for stakeholders who announce their presence in the construction or operations phases. Here, the use of overt and covert forms of power in the form of persuasion or framing, are more likely to be strategies that succeed. We therefore posit:

Proposition 1: Stakeholders in public space projects may surface throughout the project lifecycle. While stakeholders who are identified early may influence design changes, stakeholders who arrive later on are dealt with through the exercise of overt or covert organizational power tactics.

A key difference between the two cases is the governance structure used to manage the project. In the case of the park, the governance structure was rather diffuse with no clear authority. The design firm attempted to coordinate the governance of the project but lacked legitimacy. This led to a number of stakeholders interfering with the project ex-post, all of whose demands were not appeased. On the other hand, the temple renovation project exhibited more centralized control, with the sponsor as well as the religious head of the temple exercising legitimate control over project decisions. While stakeholders continued to surface through the project’s lifecycle, demands during the construction or operations phase were effectively dealt with by the sponsor or the head of the temple whose perceived legitimacy overrode these concerns. We therefore posit:

Proposition 2: Centralized control by the project integrator is likely to help definitively resolve concerns raised by stakeholders during the construction or operational phases.

While centralized networks may be better for resolving stakeholder concerns more definitively, they might not be the most feasible/desirable form of network for certain kinds of public spaces- public parks will lose their very public nature if a centralized network dominated the planning/designing of the project. Thus, a classical management approach to designing project governance networks driven by central authority and guided by a single organizational goal may not be most desirable for public space projects (Agranoff and McGuire, 1999)

Finally, we would like to highlight the relationship between the nature of the integrator and the network, and the strategies of stakeholder management used through the following proposition.

Proposition 3: In a centralized or hierarchical stakeholder network characterized by a powerful and/or legitimate integrator, the strategies used for stakeholder management are more likely to be coercive and power-driven while in a more diffused network, the integrator is more likely to use softer skills to manage diverse stakeholder interests or rely on more powerful partners to give a hand.

Conclusion

The need to manage stakeholders is well understood in the extant literature. However, what kinds of stakeholders will interfere with a project at each phase of its lifecycle is a question that still lends itself to empirical enquiry. In this paper, we hope to provide a few answers to this question and to show how the impact that such stakeholders have on the project can be moderated through selection of governance structures for public space projects as well as the presence of integrators.

However, considerable work needs to be done in order to understand the variety of organizational structures that projects sponsors can bring to bear on a project and the variety of responses that they may evoke from stakeholders, even in the narrowly constructed domain of public works projects.

References

Agger, A., Roy, P., &Leonardsen, Ø. (2016). Sustaining area-based initiatives by developing appropriate “anchors”: the role of social capital. Planning Theory & Practice, 17(3), 325-343.

Coelho, K., Kamath, L., &Vijayabaskar M. (2013) (Eds) Participolis: Consent and contention in neoliberal India. Taylor & Francis Group.

Elwood, S. (2002). Neighborhood revitalization through ‘collaboration’: Assessing the implications of neoliberal urban policy at the grassroots. GeoJournal 58, 121–130.

Elwood, S. (2004). Partnerships and participation: Reconfiguring urban governance in different state contexts. Urban Geography, 25, 755–770.

Selvaraj, K, Roy, P and A. Mahalingam (2017) Stakeholder management in public space design projects – strategies for sustainable change: the Luz Church road case in Chennai, conference paper submitted to EPOC

Roy, P. (2015) Collaborative planning – a neoliberal strategy? A study of the Atlanta BeltLine Cities, Vol 43 pg 59-68.

Healey, P. (2003). Collaborative planning in perspective. Planning Theory, 2(2),

101–123.

Innes, J. (2004). Consensus building: Clarifications for the critics. Planning Theory,

3(1), 5–20.

Forester, J. (2006). Making participation work when interests conflict: moving from facilitating dialogue and moderating debate to mediating negotiations. Journal of the American Planning Association, 72(4), 447-456.

Caniato, M, Vaccari, M., Visvanathan, C. And C. Zurbrugg (2014) Using social network and stakeholder analysis to help evaluate infectious waste management: a step towards a holistic assessment, Waste Management Vol. 34: 938-951

Bodin, O, Crona, B, and Ernstson, H. (2006) Social Networks in natural resource management: what is there to learn from a structural perspective? Ecol. Soc. 11(2) Article no. r2.

Newcombe, R. (2003) From client to project stakeholders: a stakeholder mapping approach, Construction Management and Economics (December 2003) 21, 841-848.

Holman, N., & Rydin, Y. (2013). What can social capital tell us about planning under localism? Local Government Studies, 39, 71–88.

Agranoff, R, and McGuire, M. (1999) Managing in networks settings, Policy Studies Review, Spring 1999, 16: 1.